|

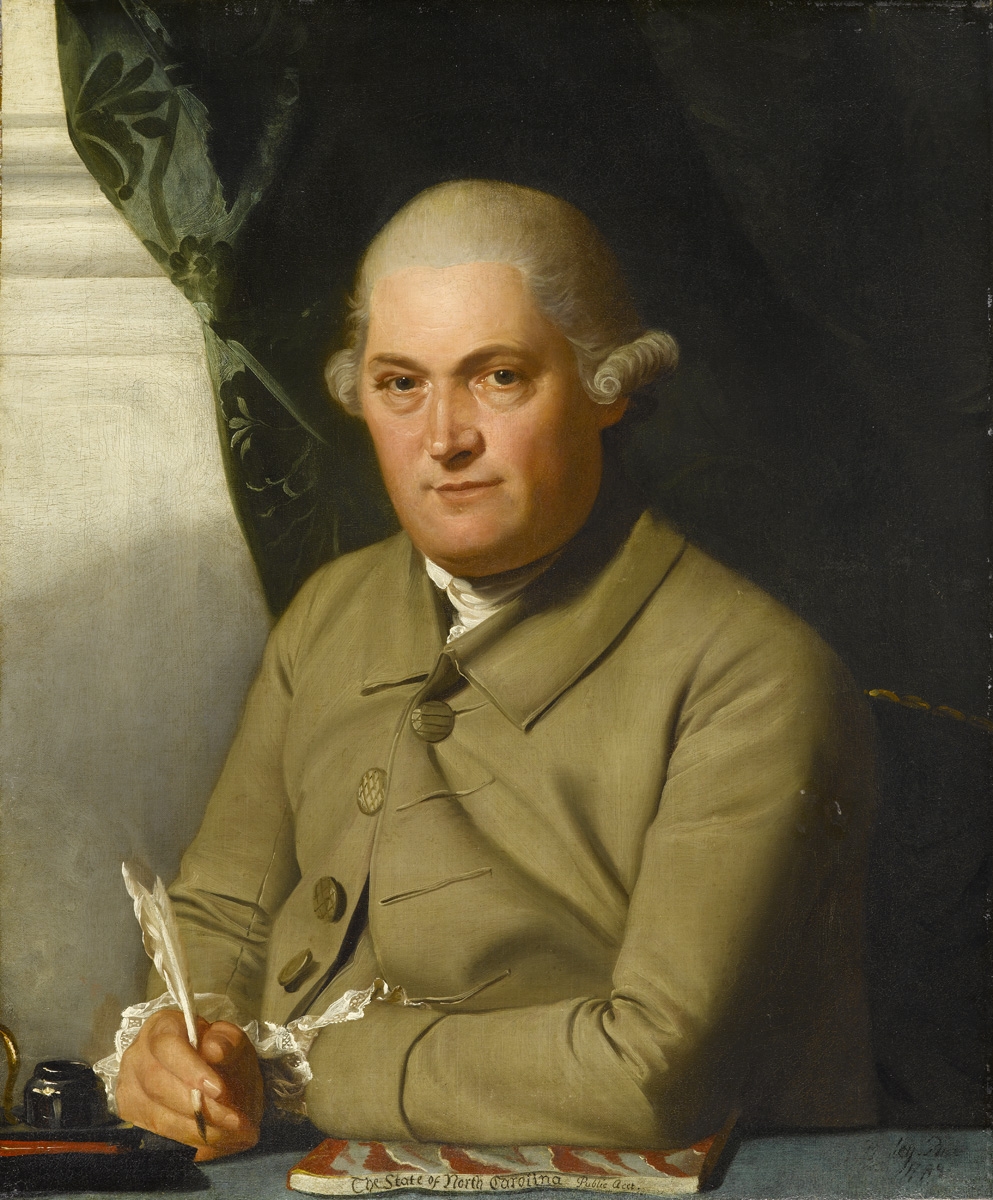

John Burgwin

Susan Bradley Wright

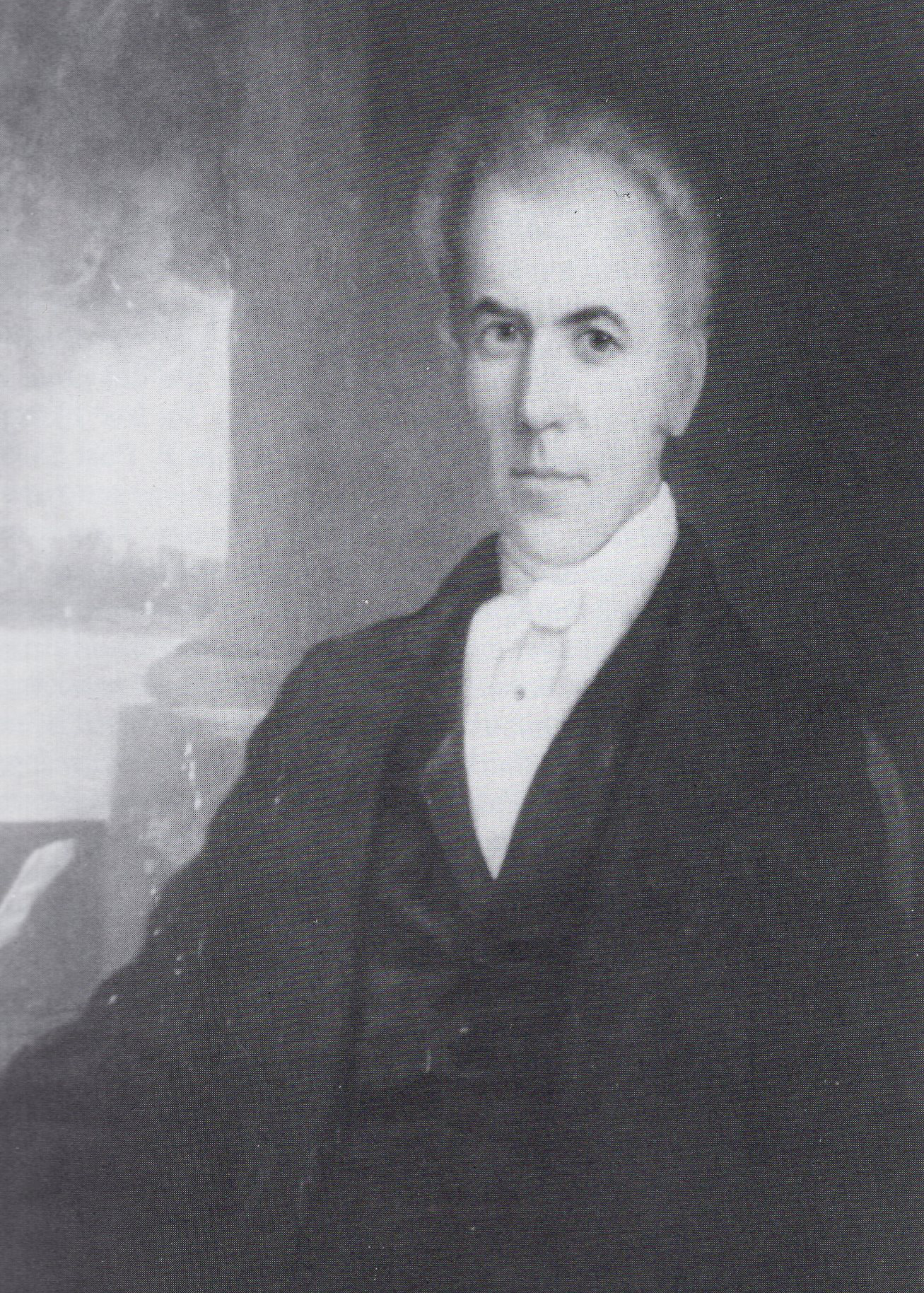

Thomas Henry Wright

|

1744-1768

The property and ballast stone buildings are operated as the first city jail (gaol) of Wilmington. The roof of the jail burned in 1768 under “suspicious circumstances,” leading the city to launch an investigation. John Burgwin offers to purchase the property in return for the jail’s relocation to the outskirts of town.

1770-1775

The Burgwin-Wright House is built as a townhouse for John Burgwin, using the ballast stone walls of the jail as a foundation for the house, and the jailer’s quarters as a detached kitchen. During his occupation of the house, John serves Wilmington as a Magistrate, Clerk of the Superior Court of Justices, Master of the High Court of Chancery, and as a Treasury official and secretary under Royal Governors Arthur Dobbs and William Tryon.

1775

After returning to England for medical care, Burgwin leases the house to his close friend and business associate Charles Jewkes, who lives here with his wife Ann Wright Jewkes, a widow formerly married to Captain Thomas Wright. Jewkes owns a sizeable warehouse downtown where he sells rum, sugar, coffee, and slaves. Ann Wright’s three children, Thomas, Mary, and Joshua Grainger Wright, are all raised here in the Burgwin-Wright House.

1799

After his stepfather, mother, and older brother pass away in quick succession, 33-year-old Joshua Grainger Wright purchases the house from John Burgwin, and lives here with his wife Susan Bradley Wright and their children Charles, Thomas Henry, John, William, Joshua, Ann and Caroline. Joshua serves as a member of the North Carolina General Assembly from 1792 to 1809, and later in life becomes a Superior Court judge and sits on the North Carolina Supreme Court from 1808 until his death in 1811.

1811

Joshua’s 11-year-old son, Thomas Henry Wright, inherits the house and continues to live here with his mother and younger siblings. After graduating from the University of North Carolina in 1820, Thomas receives his doctorate in medicine from Columbia University and returns to Wilmington in 1823 when he marries Mary Allan. Thomas is the only member of the Wright family to spend the entirety of his life, apart from his years at school, here at the Burgwin-Wright House. Always fascinated by architecture, Thomas is responsible for the 1845 enlargement and restoration of the house, and also helps design the Gothic-inspired edifice of St. James Church across Third Street. In addition, he becomes one of the first directors of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, and from 1847 until his death in 1861, Thomas serves as President of the Bank of Cape Fear. He is survived by his children Adam, Joshua, James, Allan, Mary, Susan, and Caroline.

1861

Shortly after inheriting the house from his father, Dr. Adam Empie Wright enlists in the Confederate army and serves with the 22nd Regiment of the North Carolina Home Guards as the unit’s surgeon. In July 1862, he returns to Wilmington and lives for several years with his wife, Sallie Fotterall Potter Wright, in the house after being reassigned to the New Hanover County Hospital.

1869

William H. McRary, a wealthy merchant, bank director, and director of the local gas company, purchases the house from Dr. Wright and lives here with his wife Martha. The couple have no children, and McRary passes away in 1882.

1907

After Martha McRary’s death, the house is left to her sister Rowena Wiggins, who lives alone in the house until her death in 1930.

1930

Upon Ms. Wiggin’s death, the house and property transfers to Wilmington Savings and Trust Company. Initially, New York businessman, Samuel Pryor, plans to purchase the home, dismantle it, and relocate it to Connecticut, leaving the land to Standard Oil, for a gas station. Upon hearing the news, The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the State of North Carolina (NSCDA-NC), begin a movement to preserve the colonial landmark by raising money to purchase the property. When Mr. Pryor hears about the Colonial Dames’ efforts, he has a change of heart. Abandoning his own plans, he contributes $250 to the North Carolina Dames and speaks with bank officials on their behalf.

|